An easy and safe DI (Dependency Injection) solution for Dart with support for scoping.

Introduction

A Pot is a container that creates and keeps an object of a certain type.

- Easy

- Straightforward because it is specialised in DI, without other features.

- Simple API that you can be sure with confidence how to use.

- A pot as a global variable is easy to handle, and can take help from IDEs.

- Safe

- Not dependent on types.

- No runtime error. The object always exists when it is accessed.

- Not dependent on strings either.

- Features to access an object or a scope by name were excluded on purpose.

- More of other similar design decisions for safety.

- Not dependent on types.

Policy

This package is not going to adopt new features easily so that it’ll be kept simple.

The focus will be more on enhancing stability and robustness.

Usage

Create a pot with the factory that instantiates an object.

A single pot is for a single type, which is different from most of other DI containers.

final counterPot = Pot(() => Counter(0));

Now you can use the pot wherever it is if the file containing the above declaration is imported.

Note that the created pot should be assigned to a global variable unless there is some

special reason not to.

Getting the object

You can use either get or call():

void someMethod() {

final counter = counterPot.get;

}

void someMethod() {

final counter = counterPot();

// Or

// final counter = counterPot.call();

}

Creating an object

An object is created by the factory when it is first accessed like above.

If you need to instantiate an object immediately without obtaining it, use create()

explicitly.

void someMethod() {

counterPot.create();

}

Discarding the object

You can discard the object with several methods like reset(). The resources are saved

if objects are properly discarded when they are no longer necessary.

Even if an object is discarded, the pot itself is not discarded. A new object is created when

it is needed again, so no worry that the object may have already been discarded and not be

accessible.

If a callback function is passed to the disposer of the Pot constructor,

it is called when the object in the pot is discarded. Use it for doing a clean-up related to

the object.

final counterPot = Pot<Counter>(

() => Counter(0),

disposer: (counter) => counter.dispose(),

);

void main() {

final counter = counterPot();

counter.increment();

...

// Discards the Counter object and triggers the disposer function.

counterPot.reset();

}

replace(), Pot.popScope(), Pot.resetAllInScope()

and Pot.resetAll() also discard existing object(s). These will be explained in

later sections of this document.

Advanced usage

Replacing the object factory

It is possible to replace the factory if the pot was created by Pot.replaceable.

Otherwise, the replace() method is not available.

final userPot = Pot.replaceable(() => User.none());

Future<User> signIn() async {

final userId = await Auth.signIn(...);

userPot.replace(() => User(userId));

return userPot();

}

Note that the existing object is discarded before the factory is replaced, and in the same

way as when reset() is manually used, it triggers the disposer too.

Replacing in tests

If replacement of the factory is only necessary for testing, avoid using Pot.replaceable.

It is safer to disable it if unnecessary.

Instead, enable replacement by setting Pot.forTesting to true and use

replaceForTesting().

final counterPot = Pot(() => Counter(0));

void main() {

Pot.forTesting = true;

test('Some test', () {

counterPot.replaceForTesting(() => Counter(100));

...

});

}

Scoping

A “scope” in this package is a notion related to the lifespan of an object held in a pot.

It is given a sequential number starting from 0. Adding a scope increments the index

number of the current scope, and removing one decrements it.

For example, if a scope is added when the current index number is 0, the number turns 1.

If an object is created then, it gets bound to the current scope 1. It means the object

exists while the current scope is 1 or newer, so it is discarded and the disposer is

triggered when the scope 1 is removed. The current index number is back to 0.

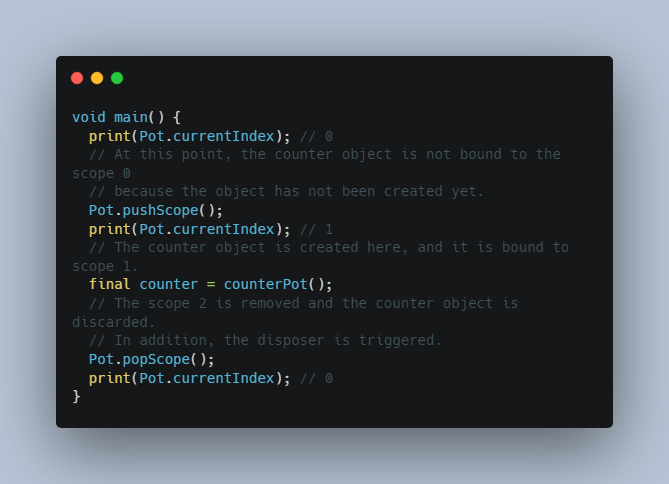

final counterPot = Pot<Counter>(

() => Counter(),

disposer: (counter) => counter.dispose(),

);

void main() {

print(Pot.currentIndex); // 0

// At this point, the counter object is not bound to the scope 0

// because the object has not been created yet.

Pot.pushScope();

print(Pot.currentIndex); // 1

// The counter object is created here, and it is bound to scope 1.

final counter = counterPot();

// The scope 2 is removed and the counter object is discarded.

// In addition, the disposer is triggered.

Pot.popScope();

print(Pot.currentIndex); // 0

}

If multiple objects are bound to the current scope, you can discard all of them by just

calling Pot.popScope().

Combining replace() with scoping

An object is not created unless it is used even if its pot is declared globally first.

So in the case where the object is used only from some point onwards, you can declare

the pot with a dummy factory initially, and replace it with the actual one at that point,

in addition to adding a scope there.

Example code (Click to open)

final todoDetailsPot = Pot<TodoDetails>(

// A dummy factory for the moment.

() => TodoDetails(),

disposer: (details) => details.dispose(),

);

class TodoDetailsPage extends StatefulWidget {

const TodoDetailsPage({required this.todoId});

final String todoId;

@override

_TodoDetailsPageState createState() => _TodoDetailsPageState();

}

class _TodoDetailsPageState extends State<TodoDetailsPage> {

@override

void initState() {

super.initState();

// A new scope is added, and the dummy factory is replaced with the actual one.

Pot.pushScope();

todoDetailsPot.replace(() => TodoDetails(widget.todoId));

}

@override

void dispose() {

// The TodoDetails object is discarded when the page is disposed of.

Pot.popScope();

super.dispose();

}

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

// The TodoDetails object specified by the todo ID is obtained.

// It gets bound to the current scope when it is first accessed here.

final details = todoDetailsPot();

...

}

}

Above is an example of an app using Flutter.

- The TodoDetails object is only necessary in the TodoDetailsPage.

- It is better to be created in the page, and discarded when the user leaves there.

- The object must be created with the todo ID.

- The dummy factory is replaced with the actual one that uses the todo ID.

Resetting objects without removing a scope

Pot.resetAllInScope() discards all the objects bound to the current scope,

but the scope is not removed. This method is likely to be only necessary in rare cases.

Similarly, Pot.resetAll() discards all the objects that are bound to any scope.

This is useful to reset all objects for testing. It may also be used for clearing the state

to make the app behave as if it restarted.

The behaviour of a reset of each object is the same as reset(), therefore the disposer

is triggered in the same way.

Caution

All pots should usually be declared globally, but it is possible to declare and use a pot

locally, as long as its object is properly discarded. Its partial data is stored globally

even if the pot is assigned to a local variable, and it is not automatically discarded

even when the variable is no longer in use. It therefore must be discarded manually with

reset() or other methods that have the same effect.

void main() {

final myClass = MyClass();

...

myClass.dispose();

}

class MyClass {

final servicePot = Pot(() => MyService());

// Use reset() in a disposing method like this

// and make sure to call it at some point.

void dispose() {

servicePot.reset();

}

void someMethod() {

final service = servicePot();

...

}

}

In Flutter, the dispose() method of the State class or a method called from there would

be the most preferable place for it.